Why Krakow?

Over the three weeks I spent here I became more and more convinced that I should move to Krakow.

Book Top Experiences and Tours in Krakow:

If youʻre booking your trip to Krakow last minute, we have you covered. Below are some of the top tours and experiences!- From Warsaw: Auschwitz-Birkenau Tour by Car

- From Krakow: John Paul II Full Day Tour - Private Transport

- Krakow: Zakopane with Hot Springs, Cable Car & Hotel Pickup

- Archdiocesan Museum in Krakow

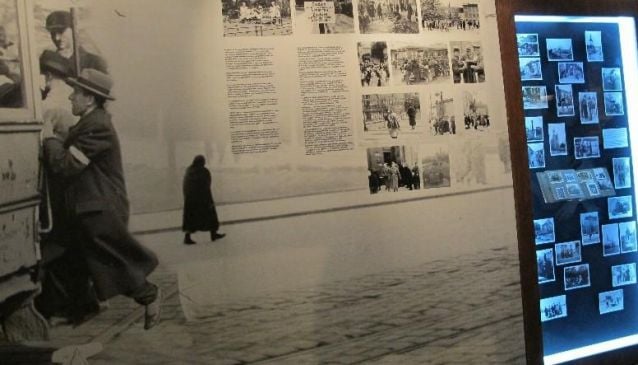

- Auschwitz-Birkenau: Skip-the-Line Entry Ticket & Guided Tour

“So tell me, Josh, why Krakow?”

If I had a potato for every time a Cracovian asked me the above question I could have opened a vodka distillery and retired on the profits long ago. To the casual visitor to this beautiful old city it must seem a very odd question, but if you choose to live here the locals will want to know why.

My first experience of Krakow was December 2003, invited by a Polish friend in London to spend Christmas with his family. This was just prior to Poland joining the EU, with LOT and BA the only (expensive) flight options. So I got to experience the 27-hour coach trip from London to Krakow that was the norm at that time for Poles travelling to and from Britain. The highlight of the trip was undoubtedly crossing the border from Germany into Poland at around dawn – sleep deprivation and a stiff neck did nothing to diminish the wonder of this strange land of snowy pines and unpronounceable signposts, the border guards evoking vague memories of Cold War spy stories. Partly due to the snow, but more so the poor roads, we didn’t arrive in Krakow until 10 that evening.

As a visitor it was a great advantage being the guest of a native, as I was shown the typical tourist sights by day while the evenings were spent at friends or, more frequently, in the bars preferred by Cracovians, such as Pauza, Singer and the late-lamented Jemjola. Life in London had lost its sparkle, and over the three weeks I spent here I became more and more convinced that I should move to Krakow.

Two years later, in the spring of 2006, I did just that. I still remembered my way around Kazimierz and the Old Town, but unlike my earlier visit the sun was out in force, the Market Square was lined with outdoor café seating and a cold beer was mandatory. I’d given myself a provisional time of six months: enough, hopefully, to get a proper feel for the place and also determine whether it was right for me. I’m a musician, and while it seems strange for many that I should leave one of the world’s major musical cities for one that isn’t even the most significant in Poland, my view was that I was trading being one tiny plankton in a vast ocean for being at least a minnow in a medium-sized lake.

The fact that I had made several Polish friends in London – many of whom had returned to Poland once it joined the EU – made it considerably easier to settle in and avoid becoming part of what I imagined to be an “expat ghetto”; although it would take longer than expected to start finding paid work in music. Before my provisional six-month period had expired I knew that I wanted to stay here; within a year I also had friends in the expat community – none of them being the embittered gin-swilling union-jack toting colonials of my over-active imagination – and had played my first paying gig.

In my first few months here, when I had encountered the Question for maybe the tenth time in a three-day period, I hit upon responding with the side-splitting reply that I had always wanted to live somewhere where the beer was expensive and the womenfolk plain (this is of course patently untrue on both counts). Amazingly, some Poles actually found this attempt at irony amusing, and it was by this somewhat clumsy effort that I learned that the frequently dour appearance of many natives masks a sense of humour that willingly embraces the ridiculous – Monty Python’s Flying Circus is arguably more popular in Poland than in its country of origin.

On a more serious note, a lot of this black humour comes from Poland’s troubled history and frequent experience of oppression and worse: much of what I now know never appeared in the history I learnt at school in England. And this perhaps points to another motivation for the Question, and one I would prefer to be untrue: that there is an underlying pessimism and sense of impending tragedy in many Poles’ minds; that there have been false dawns before; that something or someone will contrive to ruin everything; in short that the country is a mess and always will be, and only a fool would choose to live here.

This is nonsense. Although minimal investment in infrastructure in the 20th century means that there is much to be done to catch up with countries to the west of Poland, it has nevertheless eased comfortably into 21st century European life, with growing confidence in its role and importance as one of the bigger countries in the EU. As it is, today’s Krakow can offer any of the globalised commodities the modern tourist might want, while still maintaining its unique character as Poland’s cultural capital.

But for me the answer to the Question is uncomplicated. Krakow has all the advantages of a modern European city coupled with a size that is neither too big nor too small. The central areas can easily be traversed on foot, and other than churches – of which there is an abundance – there are few tall buildings to trouble the skyline. I’ve tried to resist mentioning the vast numbers of bars and clubs, which range from the charmingly anarchic to the sleekly sophisticated, but lovers of good beer should take note that all manner of small independent breweries are finding popular expression in bars such as the House of Beer in the Old Town and Omerta in Kazimierz.

When not contributing to the expansion of small independent breweries I like walking and cycling. The banks of the River Vistula are a favourite route, whether west towards the Benedictine abbey at Tyniec, or east, passing the Aircraft Museum on the way to Nowa Huta. Nowa Huta is worth seeing not just for the exercise in Socialist Realist town planning of the district itself – along with the adjacent steelworks – but also the old villages and parks on its peripheries, with historic wooden churches and medieval monasteries. Another is Podgorze, south of the river, and beyond that some marvellous rolling uncultivated parkland that goes a considerable way towards atoning for its previous incarnation as Plaszow concentration camp.

Finally, here in Krakow I can make a living from, and enjoy, my music – either playing live with my band The Beertones, who perform regularly every week in the city centre, or in various other bands. I also run a small studio, recording myself and other musicians, as well as an ongoing cooperation with a local animator producing soundtracks for her films (some of which have been featured in animation festivals across Europe). Why Krakow? I think you should have the answer by now!